Herbert Creecy

Herbert Creecy

(1939 - 2003)

Herbert Creecy lived to paint.

The Atlanta-born artist was by all accounts a vibrant, voluble and sociable man. But he found his soul's content by himself in an old cotton warehouse in Barnesville, where he made the energetic and masterful abstract expressionist canvases that were the source of his reputation as one of Georgia's most important artists.

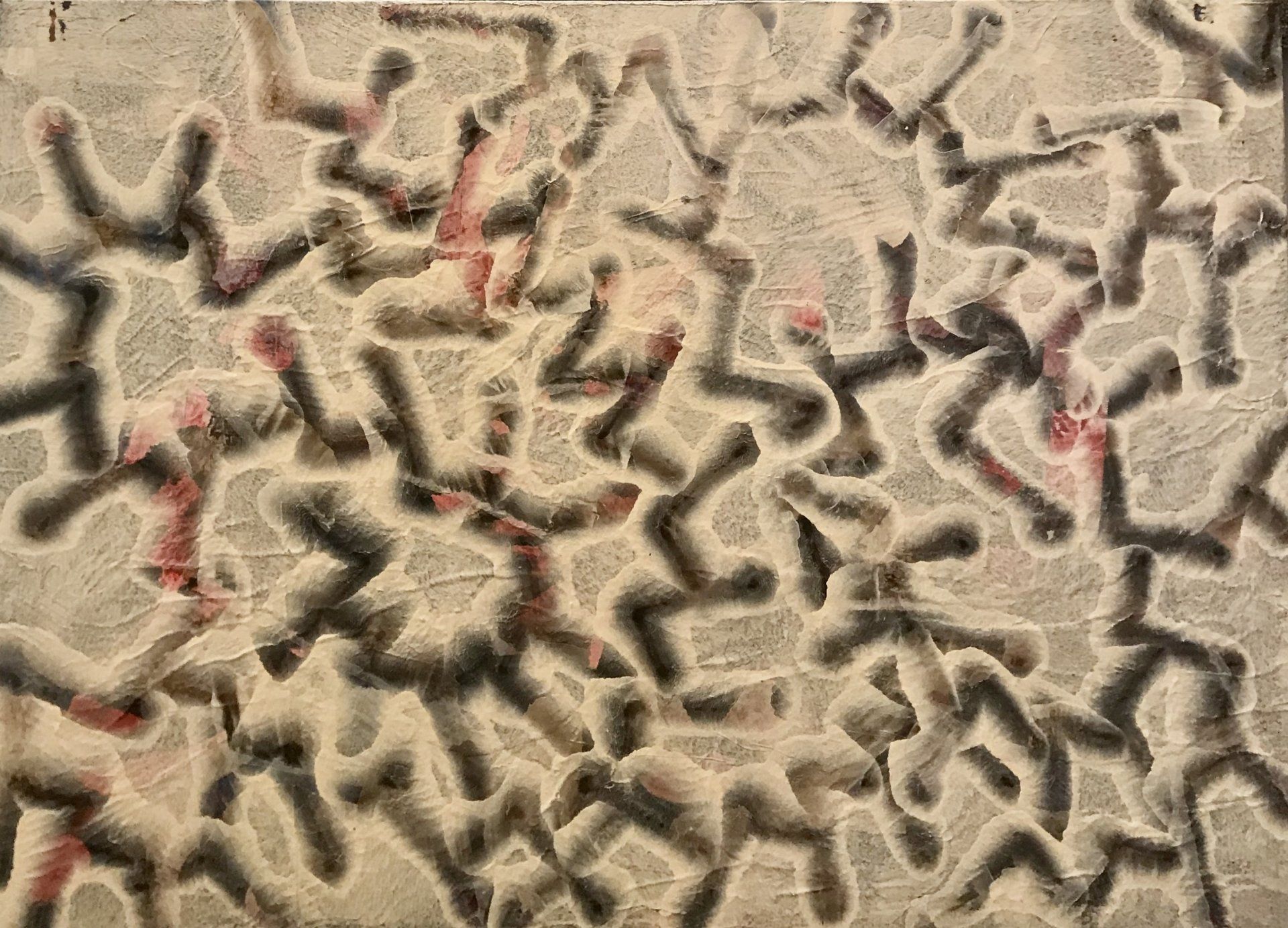

Creecy was most associated with his signature multicolor, fingerpaint-ish squiggles arrayed in dense, allover compositions. But he hardly limited himself to that approach. A constant tinkerer, he had recently experimented with applying paint through an industrial air compressor, which created doughnut shapes that melted at the edges. He incorporated scraps of old paintings as collage. His paintings could even be unexpectedly spare. And they might not be totally abstract: References to architecture and landscape were quite direct in some of Creecy's paintings, a suggestion of his connection to the region of his birth.

"He was basically a Southern artist," said Alston Glenn, a childhood friend. "To understand his paintings, I tell people to imagine they are a bird flying over the Southern landscape seeing the shanties, the fields."

Creecy worked like a demon. He had carved a living space out of his studio, so he could get up in the morning to paint or paint all night. Visitors marveled at the sheer number of canvases stacked against walls and the piles of paper studies on the floor.

"You had to step over them and squeeze in between them," recalled Karen Comer, who curated "Curves, Swerves and Repetitions," a 2002 exhibition of 23 monumental Creecy works at City Gallery East that was part of the annual Master Series, which showcases the area's greatest talent.

Although the dynamism of his paintings suggested spontaneity, any single painting might be the product of years of work. He would do a piece, paint over it, reinvent it and sign it multiple times. "War," the star of his City Gallery East show, was dated 1977-2001. The dialectic between the energy of his brush strokes and their archaeological character gave the paintings an engaging tension.

Creecy grew up in Colonial Homes apartments in Buckhead, and the friends he made at E. Rivers Elementary School --- future shakers such as Glenn, who was executive director of the Atlanta Botanical Garden after retiring from Bank South; lawyer Horace Sibley; and the Atlanta Opera's Alfred Kennedy --- would be friends for life.

Glenn recalled the inklings of Creecy's future metier in the way he made model airplanes. "He would never follow the directions, and he would paint all over them," he said.

Glenn said his friend went to the University of Alabama after Northside High School, intending to follow his father's wishes that he become a dentist, but after he took his first art course, "there was no turning back."

Creecy graduated from the Atlanta College of Art in 1964, took a fellowship at the famed Stanley Hayter print atelier in Paris, and returned to Atlanta to make his way as an artist. He carved out a niche with his big and forceful personality as well as his art. Friends describe him as cantankerous and opinionated, thoughtful and intelligent, a man who loved to discuss and debate, not only art but politics. In the early days, he and his friends could be found at the now-defunct Stein Club in Midtown, which art dealer David Heath likens to the Cedar Bar, the hangout for abstract expressionists in New York in the 1940s.

"Herb reminded me of those artists," said Heath, who represented him for many years. "Play hard, drink hard, work hard."

In fact, Jackson Pollock was Creecy's greatest influence. Pollock supplied the roots of his gestural, allover compositions and even his method of painting on the floor. Although the cool minimalism of the late Ed Ross held sway in Atlanta, Creecy, who prided himself on being different in any case, wore his emotions on his canvases.

"I could always tell what was going on in his life by his paintings," said Glenn. "When things were tough, the colors would be gray, like storms coming in. When things were good, it was like sunshine on red clay."

An aura of legend surrounded Creecy: He was the artist who chose the South over fame and fortune. Certainly, in the 1970s, national recognition seemed to be coming his way. New York's Whitney Museum of American Art acquired one of his paintings, and his work was included in the 1977 Biennial of the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington. He was briefly represented by OK Harris Gallery in New York. Moving to Barnesville seemed to signal that he was not going to play the careerist game.

Whatever might have been, there is no denying what is: powerful paintings that celebrate the artistic process and the physicality of paint. Laura Lieberman, who wrote the catalog essay for the City Gallery East show and was a longtime friend, considers the artist a great role model.

"He demanded incredibly high standards for himself in Barnesville," she said. "He defines the validity of being in the South."

Herbert Creecy lived to paint.

The Atlanta-born artist was by all accounts a vibrant, voluble and sociable man. But he found his soul's content by himself in an old cotton warehouse in Barnesville, where he made the energetic and masterful abstract expressionist canvases that were the source of his reputation as one of Georgia's most important artists.

Creecy was most associated with his signature multicolor, fingerpaint-ish squiggles arrayed in dense, allover compositions. But he hardly limited himself to that approach. A constant tinkerer, he had recently experimented with applying paint through an industrial air compressor, which created doughnut shapes that melted at the edges. He incorporated scraps of old paintings as collage. His paintings could even be unexpectedly spare. And they might not be totally abstract: References to architecture and landscape were quite direct in some of Creecy's paintings, a suggestion of his connection to the region of his birth.

"He was basically a Southern artist," said Alston Glenn, a childhood friend. "To understand his paintings, I tell people to imagine they are a bird flying over the Southern landscape seeing the shanties, the fields."

Creecy worked like a demon. He had carved a living space out of his studio, so he could get up in the morning to paint or paint all night. Visitors marveled at the sheer number of canvases stacked against walls and the piles of paper studies on the floor.

"You had to step over them and squeeze in between them," recalled Karen Comer, who curated "Curves, Swerves and Repetitions," a 2002 exhibition of 23 monumental Creecy works at City Gallery East that was part of the annual Master Series, which showcases the area's greatest talent.

Although the dynamism of his paintings suggested spontaneity, any single painting might be the product of years of work. He would do a piece, paint over it, reinvent it and sign it multiple times. "War," the star of his City Gallery East show, was dated 1977-2001. The dialectic between the energy of his brush strokes and their archaeological character gave the paintings an engaging tension.

Creecy grew up in Colonial Homes apartments in Buckhead, and the friends he made at E. Rivers Elementary School --- future shakers such as Glenn, who was executive director of the Atlanta Botanical Garden after retiring from Bank South; lawyer Horace Sibley; and the Atlanta Opera's Alfred Kennedy --- would be friends for life.

Glenn recalled the inklings of Creecy's future metier in the way he made model airplanes. "He would never follow the directions, and he would paint all over them," he said.

Glenn said his friend went to the University of Alabama after Northside High School, intending to follow his father's wishes that he become a dentist, but after he took his first art course, "there was no turning back."

Creecy graduated from the Atlanta College of Art in 1964, took a fellowship at the famed Stanley Hayter print atelier in Paris, and returned to Atlanta to make his way as an artist. He carved out a niche with his big and forceful personality as well as his art. Friends describe him as cantankerous and opinionated, thoughtful and intelligent, a man who loved to discuss and debate, not only art but politics. In the early days, he and his friends could be found at the now-defunct Stein Club in Midtown, which art dealer David Heath likens to the Cedar Bar, the hangout for abstract expressionists in New York in the 1940s.

"Herb reminded me of those artists," said Heath, who represented him for many years. "Play hard, drink hard, work hard."

In fact, Jackson Pollock was Creecy's greatest influence. Pollock supplied the roots of his gestural, allover compositions and even his method of painting on the floor. Although the cool minimalism of the late Ed Ross held sway in Atlanta, Creecy, who prided himself on being different in any case, wore his emotions on his canvases.

"I could always tell what was going on in his life by his paintings," said Glenn. "When things were tough, the colors would be gray, like storms coming in. When things were good, it was like sunshine on red clay."

An aura of legend surrounded Creecy: He was the artist who chose the South over fame and fortune. Certainly, in the 1970s, national recognition seemed to be coming his way. New York's Whitney Museum of American Art acquired one of his paintings, and his work was included in the 1977 Biennial of the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington. He was briefly represented by OK Harris Gallery in New York. Moving to Barnesville seemed to signal that he was not going to play the careerist game.

Whatever might have been, there is no denying what is: powerful paintings that celebrate the artistic process and the physicality of paint. Laura Lieberman, who wrote the catalog essay for the City Gallery East show and was a longtime friend, considers the artist a great role model.

"He demanded incredibly high standards for himself in Barnesville," she said. "He defines the validity of being in the South."

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal & Constitution

- Untitled circa 1990

- 17-1/2" x 23"

- Acrylic on Paper

- Signed and Dated on Verso

- $8,000.00

- Untitled circa 1993

- 36" x 36"

- Acrylic on Canvas

- Signed and dated on verso by artist

- $40,000.00

- Untitled circa 1993

- 46" x 46"

- Acrylic on canvas

- Signed and dated on verso by artist

- $50,000.00

- Altamaha Shade circa 1990-1999

- 31" x 44"

- Acrylic on Canvas

- Signed and dated on verso by artist

- $45,000.00

- Pressure from the Vail circa 1980-2001

- 29" x 27"

- Acrylic on Canvas

- Signed and dated on verso by artist

- $35,000.00

View more

© 2025

All Rights Reserved | Avery Gallery, Inc.